The law-making process in England and Wales

Use 'Print preview' to check the number of pages and printer settings.

Print functionality varies between browsers.

Printable page generated Tuesday, 16 April 2024, 1:52 PM

The law-making process in England and Wales

Introduction

This OpenLearn course introduces you to the different sources of law in England and Wales. The course begins by providing an overview of the different sources of law. It then considers what is meant by democracy and how and by whom proposed legislation is initiated, before introducing you to the Westminster Parliament, which creates legislation. It is within this Parliament that proposed legislation – known as a Bill – is considered and becomes law.

In this course different forms of legislation are introduced, such as statutes and statutory instruments (otherwise known as delegated legislation), together with the reasons why certain powers are delegated and how this legislative system operates. Section 8 of this course provides you with a further opportunity to learn about devolution and the developments that have taken place in Wales. It outlines the devolvement (transfer) of powers from the Westminster Parliament to the Welsh Assembly (The Senedd). As this course concentrates on England and Wales, the primary focus when dealing with devolution is on Wales.

The course develops your research and critical thinking skills by introducing you to different forms of legislation. The activities included in this course provide you with an opportunity to locate an Act of Parliament and consider the layout (structure) of a statute. You will consider how legislation controls certain types of behaviour or social interaction in society, such as excluding certain liability in contract law or imposing liability for certain types of anti-social behaviour.

This OpenLearn course is an adapted extract from the Open University course W101An introduction to law.

Learning outcomes

After studying this course, you should be able to:

explain the roles played by various individuals and bodies who may instigate legislative proposals

discuss the legislative process in the Westminster Parliament

distinguish between primary and secondary legislation

explain the structure of a piece of legislation and discuss its application in context

explain what is meant by devolution and explain how devolution has evolved in Wales.

1 An overview of the sources of law

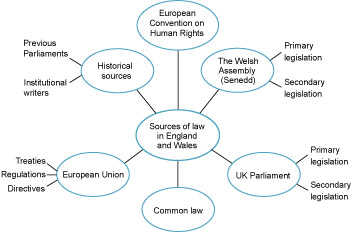

This course introduces you to one of the three main sources of law in England and Wales – that is, statute law, also referred to as legislation. The other two main sources of law are European (EU) law and case law. Figure 1 illustrates the sources of law which govern England and Wales.

This figure is a diagram. The text inside the central circle states ‘Sources of law in England and Wales’. Outside this circle are six separate circles which surround the central circle like the numbers of a clock. Starting with the first outer circle, which is positioned where the number 12 would appear on a clock, and moving clockwise, each of the six circles identifies a source of law as follows: European Convention on Human Rights, The Welsh Assembly (Senedd), UK Parliament, Common law, European Union and Historical sources.

Some of the outer circles have a number of branches with sub-categories. The Welsh Assembly (Senedd) has two branches: primary legislation and secondary legislation. The UK Parliament has two branches: primary legislation and secondary legislation. The European Union has three branches: treaties, Regulations and Directives. The Historical sources circle has two branches: previous parliaments and institutional writers.

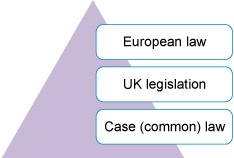

It is important to know how these sources of law are created and how they operate in the legal system in England and Wales. Being able to identify the sources of law and the order of ranking is important. These sources are hierarchical and rank in the following order:

A picture of a triangle. The triangle is symbolic as it represents the hierarchy of the three sources of law from top to bottom. On the right-hand side of the triangle there are three oblong boxes on top of each other in a vertical position. Within each box is written text. In the top box is the text ‘European law’, in the middle box is the text ‘UK legislation’, and in the bottom box is the text ‘Case (common) law’.

Given the hierarchical application of the three main sources of law, you need to be able to discuss the legal rules that apply in different situations. When dealing with a problem or essay question, you may need to consider whether the matter is controlled by EU law, by UK legislation or is governed by a previous decision of a court in England and Wales. Dealing with these sources of law and saying which source will prevail is important.

2 Democracy

It is important to be able to explain what is meant by democracy and to be able to discuss the issues surrounding devolution in Wales. A number of changes have taken place since 1999 which devolved (transferred) some of the law-making powers from the Westminster Parliament to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Devolution in the UK is ongoing and this course will develop the discussion by examining the role of the National Assembly in Wales (the Senedd) and how the Assembly Members (AMs) are a democratically elected body.

2.1 The notion of democracy

What is democracy? This is a difficult question to answer at this stage of the course but think about the society you live in and whether the laws that govern you reflect your views and values. Democracy is, in theory, about being treated fairly and being able to say how you are governed. This means that every citizen should be able to participate in a democratic process, allowing them to be part of the law-making process. Do you live in a democratic society? You will be able to consider this question in more depth while reading and completing the tasks dealing with democracy and the law-making process.

2.1.1 The rights provided by Magna Carta

The introduction of the Magna Carta in 1215 outlined the position of the monarchy and the people of Britain. The Magna Carta provided rights, such as the right to a fair trial. It also subjected the monarch to the rule of law, which ensured that everyone was subject to the law. This supported the development of the common law system and the beginning of democracy in the UK.

Since the Magna Carta was created, the UK legal system has developed a framework that should enable citizens of the UK to express their views and have a voice during the creation of the legal rules. This course will enable you to be able to explain how these legal rules are created and who creates them. In order to achieve this understanding you need to consider the notion of democracy. The possible contexts for considering and exploring the notion of democracy include the idea of an elected body representing you in the Westminster Parliament and/or through one of the legislative bodies in Wales, Northern Ireland or Scotland.

Activity 1 Democratic questions

Watch this short film on how power is controlled in a democratic society. Make some brief notes on the idea of representative democracy, on government and on Parliament in the UK.

Transcript: Activity 1 Democratic questions

[LAUGHTER]

[LAUGHTER]

[LAUGHTER]

[CAR ALARM]

Now, explain in your own words:

- a.what a democratic society is

- b.what a government is

- c.the difference between the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

Comment

A democratic society tries to ensure everyone is treated equally and fairly. The rule of law applies to everyone and no one is above the law. The will of the people is reflected in the legislation that is created by a legislative body, such as the Westminster Parliament, which is made up of two Houses: the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

A democratic society will prevent a dictatorship. A very simple definition of dictatorship is that power is vested in one person who decides how a country is run. The will of the people is ignored when you have a dictator, whereas a democratic society is based on the principle that a system is in place to elect individuals to represent you in a parliament.

The voting system in the UK allows every UK citizen who is over the age of 18 to vote for a candidate who is standing as a Member of Parliament, unless they are subject to any legal incapacity to vote, such as a person who has been found guilty of a crime and is either serving a prison sentence or being detained while waiting to be sentenced. It is through Parliament that new laws are made and old ones repealed. Parliament is made up of the House of Commons and the House of Lords. Members of the House of Commons are elected by those citizens in the UK who vote during the general election. Members of the House of Lords are not elected: they are either appointed through a committee or are life peers. The House of Lords will be explained in more detail as you progress through this course.

The political party which obtains the most votes during the general election will be invited by the monarch to form a government. The government is a separate political entity from Parliament. The government is responsible for the running of the country, creating and implementing any policies and drafting new legislation. Parliament is responsible for holding the government to account, checking proposed legislation, and debating and approving or rejecting new legislation.

It is the role of the first minister, who is commonly known as the Prime Minister, to take responsibility for forming the government and to appoint members of the government to take responsibility for specific areas, such as health or education.

You have now considered what a democracy is and how a democratic process forms part of what might be considered to be a fair and just society. The democratic process as it operates in the UK will now be explored.

3 The Westminster Parliament

The Westminster Parliament consists of two chambers, sometimes referred to as two Houses: the House of Commons and the House of Lords. Most modern democratic societies have two debating chambers in their central legislative body. This is referred to as a bicameral parliament, as opposed to a unicameral parliament, which only has one legislative assembly, such as the Welsh Assembly. In theory the Westminster Parliament has a third element to the law-making process: the monarch, who is referred to as the head of state. The monarch maintains the right to veto proposed legislation by withholding Royal Assent. Royal Assent is the monarch’s signature on the piece of proposed legislation once it has completed all its parliamentary stages. Today, Royal Assent is a mere formality which is undertaken on behalf of the monarch. The monarch can provide Royal Assent in person but this rarely happens. In theory the monarch may refuse to give Royal Assent but this has not occurred since 1707 when Queen Anne refused to give Royal Assent for a Bill that was dealing with the regulation of the settling of the militia in Scotland. The last time a monarch provided Royal Assent in person for a proposed Bill was in 1854.

3.1 The House of Commons and the House of Lords

It is within these two Houses that proposed legislation, known as a Bill, is discussed and debated at length. The process is prescriptive, which means the procedure is strict and follows a specific time frame and set of actions.

A picture of the two chambers of the Westminster Parliament. On the left-hand side is a picture of the interior of the House of Commons chamber: there are a number of Members of Parliament sitting or standing in this chamber. To the right-hand side is a picture of the interior of the House of Lords chamber: a number of members of the House of Lords are sitting down.

House of Commons

The individuals in the House of Commons who participate in parliamentary debate are referred to as members of the House of Commons, otherwise known as Members of Parliament (MPs). The House of Commons is considered to be the most important chamber of the Westminster Parliament as members of this chamber have been elected by their constituents in a general election, which usually takes place every five years. Each MP represents a specific constituency when attending the House of Commons. Each MP is either a member of a political party, such as the Conservative party, Labour party, Liberal Democrats or one of the smaller parties. Alternatively, an MP does not have to be a member of a party and can be an independent MP. Each party or independent MP will have a (distinctive) position on political issues, which is reflected in their party manifesto. It is the manifesto which outlines the purpose and objectives of the political party, and the proposed changes they will bring about through new legislation if they are elected. It is the party with the majority of seats (MPs) which goes on to form a government. However, if a general election does not provide a political party with a large enough majority of MPs to form a government, two political parties may join together to form a government. It is the government who decides the policies of the UK and how these policies should be implemented through the introduction of new laws, or by amending existing legislation. It is these policies which become draft legislation, which will eventually be presented to the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

Members of the House of Commons are allowed to put forward questions to government ministers in the House of Commons during a session referred to as ‘question time’. The question time session usually takes place during the first hour of business in the House of Commons each day. The government is obliged to respond to these questions and the answers are published in a transcript known as Hansard, which is an official record of what is said in Parliament.

Take a tour of the House of Commons by listening to this audio recording, which is accompanied by a selection of pictures.

Transcript: House of Commons

House of Lords

Members of the House of Lords are not elected and are made up of peers, who have been appointed by the House of Lords Appointment Commission (HLAC), and life peers. The HLAC is an independent body which was established by the then Prime Minister, Tony Blair, in 2000. Peers have a wide range of knowledge through experience gained during their professional careers, such as in the legal or academic professions, business, health and in various roles in public service. They utilise their occupational experience by contributing to matters which are debated in the House of Lords, such as education, health and public services. The function of the House of Lords is important as it contributes to the democratic process by scrutinising and revising proposed legislation that has been proposed by the current government, but as you will see later on in this course their power to block legislation is curtailed by the Parliament Acts 1911 and 1949.

Members of the House of Lords do not have to be in a political office, such as being a member of a political party and, therefore, do not have to adhere to the convention of being either collectively responsible for a party policy or supporting proposed legislation. They may have a personal political persuasion and have previously held a ministerial role within a political party but this does not take away their independence as a member of the House of Lords. This places them in a position where they may either support or challenge a piece of proposed legislation by holding the government of the day to account, by questioning the MPs and undertaking formal enquiries which relate to the specific aspects of the new legislation. However, although members of the House of Lords may delay proposed legislation and bring the matter to the attention of the media and general public, they cannot defeat a piece of legislation. The reasoning behind this position, which is outlined below, is that members of the House of Lords are not democratically elected to this chamber. Whether a piece of legislation succeeds should be according to the will of the people, which is represented in the House of Commons and not by the members of the House of Lords. The bicameral structure of Parliament – the House of Commons and the House of Lords – produces a checks and balance system whereby power is not held by one body: the principle is that there should be transparency during the debate of any proposed legislation.

3.2 The Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949

The House of Commons may use existing legislation – such as the Parliament Acts of 1911 and 1949 – which will allow them to make law without the consent of the House of Lords. This rarely happens, but the House of Commons has this power available if the House of Lords cannot reach an agreement, or rejects a piece of proposed legislation which the House of Commons wishes to bring into force. The Parliament Acts were used when the government of the day pushed through the War Crimes Act 1991, the European Parliamentary Elections Act 1999, and the Hunting Act 2004. The last of these Acts outlawed the hunting of wild animals using dogs to locate and kill the animal (usually a fox). This was a controversial piece of legislation and the House of Lords was not able to sanction the proposed Bill.

Activity 2 Fitting the Bill

Watch the following film, which discusses the work of the House of Lords when dealing with a public Bill. A public Bill is a piece of legislation which has been proposed by the government of the day.

While watching, make some notes on the different stages (order of events) which the Bill passes through. You will discover that there are a set number of stages the Bill must go through before it is then passed back to the House of Commons.

Transcript: Activity 2 Fitting the Bill

Now drag and drop the explanations given below to the right stage.

First reading

The long title is read.

Second reading

The subject is debated.

Committee stage

Each line of the Bill is looked at and amends made.

Report stage

Each line of the Bill is looked at again and further amends made.

Third reading

The Bill is tidied up.

Using the following two lists, match each numbered item with the correct letter.

First reading

Second reading

Committee stage

Report stage

Third reading

a.The long title is read.

b.The Bill is tidied up.

c.Each line of the Bill is looked at again and further amends made.

d.The subject is debated.

e.Each line of the Bill is looked at and amends made.

- 1 = a

- 2 = d

- 3 = e

- 4 = c

- 5 = b

Comment

This is the process that takes place in both Houses (the House of Commons and the House of Lords) before the Royal Assent is given. You will learn more about these stages later on in this course.

3.3 The function of each House

You are now aware that the role of each chamber (House) is to debate the proposed legislation as it goes through various stages. At this juncture you only need to be aware of the framework of the Westminster Parliament, how legislation is initiated and who will consider the proposed legislation. You also need to be aware that there is a given rule, referred to as a convention, that parliament cannot bind its successors. This means that a new political party that comes to power will be allowed to revoke and change the laws enacted by the last government in power. This convention ensures that a new government’s legislative powers are not limited. It is legislation that is the dominant law-making method in contemporary times. This is why, as a student of law, it is important to have a strong understanding of the legislative process.

4 Does the Westminster Parliament demonstrate a democratic process?

The make-up of the Westminster Parliament is part of a democratic process but if a governing party has a large majority of seats (MPs) in the House of Commons this means that a political party with the majority of voting power will be in a dominant position. If this happens the legislative process will be controlled by those with the majority of votes. In such circumstances where the majority voting power is with one political party it can be argued that democracy is reduced as the wishes of the opposition parties, and the electorate who voted for them, might be ignored. An example of this is when a government’s proposed legislation has little opposition due to the large majority of the controlling party.

Activity 3 Proportioning democracy

Watch this film, which deals with the general election in the UK. It outlines the democratic process and how political parties persuade voters (the electorate) to vote for them. Make some short notes while watching the film.

Transcript: Activity 3 Proportioning democracy

[CHEERS]

Now write a short explanation of no more than 400 words explaining the following:

- a.the purpose of the UK general election

- b.how the laws made in the Westminster Parliament may be said to reflect the will of the people in the UK

- c.the difference between first-past-the-post and proportional representation.

Comment

You may have selected a number of points from this film but some of the salient points are as follows:

- The UK has created a first-past-the-post electoral system, which means that within each constituency in the UK the candidate who has received the most votes takes the parliamentary seat in the Westminster Parliament.

- The political party with the most seats will win the general election and form the next government.

- The alternative system, which has been argued for by some political parties, is proportional representation (PR). PR does not ignore the votes cast by the electorate for those MPs who did not gain a seat in Parliament. Rather, PR would reflect these votes by ensuring the distribution of seats in Parliament would reflect the proportion of the total votes cast for each party. PR would benefit small parties by increasing their likelihood of gaining a seat but may also lead to a situation where there is no one party with a majority of seats. In this case, two or more political parties would need to join together in order to form a government, which is referred to as a coalition. For example, no single party had a majority in the 2010 election, which led to a Conservative and Liberal Democrat coalition government.

- On 5 May 2011 the Parliamentary Voting Systems and Constituencies Act 2011 allowed for a referendum to take place on whether or not to change the way Members of Parliament are elected to the House of Commons. The following question was placed on the ballot paper: ‘At present, the UK uses the “first past the post” system to elect MPs to the House of Commons. Should the “alternative vote” system be used instead?’ (Parliament, n.d.). The outcome of the referendum was: 32% voted yes and 68% voted no. The first-past-the-post system was to remain.

- The legislation introduced and debated in the Westminster Parliament is undertaken by MPs who were elected by the British public. The MPs should act on behalf of the people in the UK by introducing and passing legislation which reflects the wishes of the citizens in the UK. However, as the UK uses a first-past-the-post electoral system, there is an argument that not all the views of citizens in the UK are being reflected in the current legislation that is produced and brought into force.

5 Pre-parliamentary process

To understand how a piece of legislation is created you need to know the process that takes place prior to legislation being considered by both Houses of the Westminster Parliament. The majority of legislation that becomes law in the UK is proposed by the government, which will have outlined some of its proposals for new legislation in its party manifesto. A manifesto is a document which outlines a political party’s policies and aims. A party’s manifesto is made available by the government, which produces its manifesto during the general election. It outlines most of the proposed legislation, which is included in the Queen’s Speech at the opening of each session of Parliament.

5.1 Different types of Bills

Draft legislation is referred to as a Bill, which is considered by both chambers (the House of Commons and the House of Lords) in Parliament. The proposal for new laws can originate from an MP or one of the lords who sit in the House of Lords. There are different types of Bills. For example:

- public Bills

- private members’ Bills.

A public Bill will have an effect on the general population and this is the type of Bill which is introduced by a government minister. A Bill known as a private member’s Bill is introduced by an MP or lord but they are not government ministers. The Bill, if it goes on to become law, will affect the general population – just like a public Bill.

A number of private members’ Bills are usually instigated by pressure groups who consult with a Member of Parliament. This is referred to as lobbying. These pressure groups may take the form of professional bodies or voluntary organisations that monitor current issues which may trigger a private member’s Bill. It is important to know and understand the role pressure groups play in promoting new forms of legislation. The next section of this course will consider in more detail the role of a pressure group and the introduction of a private member’s Bill.

5.2 Pressure groups

The usual route for the electorate to engage in politics is through the voting system by electing their chosen MP. However, many individuals form organisations known collectively as pressure groups. These groups lobby MPs on various social issues and call for the introduction of new laws. An example is the debate dealing with the ban on smoking in private vehicles while children are present.

Box 1 Debate dealing with the ban on smoking in private vehicles while children are present

The pressure group Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) has campaigned against smoking in public places and also believes smoking in a private vehicle where children are present should be banned. ASH has engaged the assistance of the All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Smoking and Health. The APPG on Smoking and Health is made up of MPs and peers (lords) and was founded in 1976. Its main role is to monitor the impact tobacco products have on health and put forward measures which will reduce any health risks/hazards.

All-party groups such as the APPG on Smoking and Health are run by members of the House of Commons and the House of Lords but do not have an official status within Parliament. Rather, their role is to liaise with individuals and organisations outside Parliament, such as the pressure group ASH. In this instance, the APPG on Smoking and Health has undertaken an inquiry and produced a report on the risks associated with smoking tobacco products in private vehicles where children are present, and the effect of this upon their health. This report clearly outlines the danger of smoking in a confined space and the direct effect this has on children.

Activity 4 Parliament on health: the dangers of smoking

Extracts

Read the extracts below which have been taken from the All Party Parliamentary Group on Smoking and Health (2011) Inquiry, which deals with smoking in private vehicles where children are present.

About the Inquiry

The All Party Parliamentary Group on Smoking and Health launched this Inquiry in response to the Smoking in Private Vehicles Bill 2010–11, introduced to parliament by Alex Cunningham MP under the Ten Minute Rule. The aim of the bill is to ban smoking in private vehicles where there are children aged under 18 present.

The bill had its first reading in the House of Commons on 22nd June 2011 and was supported by 78 votes to 66 against. The APPG was keen that the best available evidence should inform the debate stimulated by the bill and in particular the second reading, scheduled for 25th November. The purpose of this Inquiry was therefore to examine the most up-to-date evidence on the harm caused by smoking in cars and the regulatory issues raised by the proposed legislation.

APPG Inquiry Findings, Conclusions and Recommendations

Background

- In March this year the coalition government launched Healthy Lives, Healthy People: A Tobacco Control Plan for England. The plan identifies the serious harm of secondhand smoke and acknowledges that ‘people are today most likely to be exposed to the harmful effects of secondhand smoke in their own homes and private motor vehicles’. However, the plan stopped short of proposing new legislation to deal with this issue, opting instead for a voluntary approach to promoting behaviour change. In this spirit, a marketing campaign is planned for spring 2012 to remind smokers of the harms of secondhand smoke and to encourage smokers to make their homes and cars smokefree.

- The government’s strategy was published at a time when the public debate on smoking in cars had already broached the options of legislative change. In March 2010 the Royal College of Physicians called for the banning of smoking in all vehicles in its report Passive Smoking and Children. Later that year the British Lung Foundation launched its Children’s Charter campaign with a focus on protecting children from secondhand smoke. The campaign includes a petition calling for smoking in cars to stop where children under the age of 18 are present.

- This year the Royal College for Paediatrics and Child Health called for all cars carrying children to be smoke free while the British Medical Association voted to support a ban on smoking in private vehicles regardless of who is present as they considered this to be safest for children, easiest to enforce, and the most effective option.

- This is an issue of great public interest with a growing evidence base. The Ten Minute Rule Bill introduced by Alex Cunningham MP in June this year has provided a clear focus for debate on this issue. The APPG is eager to ensure that this debate is informed by the best available evidence and addresses the practical and ethical issues raised by the legislation. These are the concerns of the Inquiry.

- The APPG notes that the Welsh Government has followed a similar route to the coalition government in Westminster by choosing to pursue a mass media campaign focused on stimulating changes in smokers’ behaviour in cars with children. However, the Welsh Government has stated its intention to legislate if the campaign is ineffective. The Northern Ireland Executive has gone further and committed to a consultation which is due to be completed by spring 2012.

The harm caused by smoking in cars

Findings and Conclusions

6. Smoking in cars causes several distinct harms. Firstly, there is the harm to the smoker from inhaling tobacco smoke. Secondly, there is the harm to other adults and children in the vehicle from inhaling secondhand smoke. Thirdly, there is the potential harm to children and young people from witnessing smoking as normal adult behaviour, as this increases the risk of smoking uptake. Finally, there is the potential harm to the driver, passengers and other road users from the driver’s temporary loss of full control of the vehicle.

...

15. Although it is difficult to identify the specific health impacts of secondhand smoke within cars, because people exposed within cars also tend to be exposed within the home, it is logically evident that the risk of harm is likely to be high, given the severity of the hazard and the scale of the exposure.

16. Children and young people are also affected by witnessing smoking as a normal adult behaviour. Children who live in households where adults smoke are much more likely to become smokers themselves than children growing up in non-smoking households. For every 10 children from non-smoking households who start smoking, 27 children from households where both parents smoke will start smoking themselves. Overall, if there is any smoker in a household, the likelihood that children within the household will start smoking is almost doubled. This modelling effect is responsible for about 20,000 young people becoming smokers by the age of 16 every year.

17. Smoking also affects driving safety. The Highway Code identifies smoking as one of several distractions that compromise safe driving. Unlike the use of mobile phones, smoking by drivers remains permitted. Yet the ‘inattentional blindness’ caused by using a mobile phone is also experienced when carrying out smoking-related tasks such as finding and preparing cigarettes, lighting up, and extinguishing the cigarette. International evidence demonstrates that the distraction created by smoking increases the risk of having a motor vehicle accident.

18. Although the evidence for these many harms is clear, care is needed in developing policy responses in order to avoid unexpected adverse outcomes. For example, critics of the ban on smoking in public places argued that it would result in an increase in children’s exposure to secondhand smoke in the home. In fact, this outcome did not occur: reductions in exposure to secondhand smoke have been observed in both public and private places since the enactment of smokefree legislation.

Now answer the following questions:

Question (a)

- (a) Do you think it is right to ban smoking in a private space, such as a vehicle?

Comment

This is a personal response and you may have said either ‘yes’ or ‘no’. The argument in favour of the ban relates to the dangers tobacco smoke poses for children in a confined space, such as a private vehicle. The alternative view is that smoking tobacco is not an illegal activity: why should the state control what you do in private?

Question (b)

- (b)What do you think are the main arguments for not introducing legislation banning smoking in a private vehicle while a child is present?

Comment

Again, there will be a mixture of responses but some of the arguments against this ban will relate to privacy and the right to smoke in your own personal space. A car, for instance, is a private space: should the legislature tell people how they should behave in private? This is the type of question that is raised when dealing with legislation that will tell people what they are not allowed to do in private.

Question (c)

- (c) If you are a smoker, would you stop smoking in a private vehicle while a child is present?

Comment

This will be a personal response and it depends upon the individual and how they perceive the risks and feel about the proposed legislation.

Below is an extract taken from the All Party Parliamentary Group on Smoking and Health (2011) Inquiry: the inquiry dealt with the issue of second-hand smoke (SHS) in cars. They found there was a significant increase in SHS when a single cigarette was smoked inside a car. If the proposal became law it would be an offence to smoke in a private vehicle where a child is present but then it is up to the state to police (enforce) this law.

2.0 It is well established that secondhand smoke (SHS) is a significant health hazard, and this has been the starting point for the creation of laws to reduce/eliminate SHS in public places, including the United Kingdom’s own comprehensive smoke-free laws. But there are other important venues where SHS can reach levels that are much higher than in pubs, where smoking is already banned. Most notably, this includes smoking in cars. A study published in 2009 found that just a single cigarette smoked in the small interior space of a car produced levels of secondhand smoke over 11 times greater than that of the average pub where smoking was allowed. Standard strategies for reducing SHS in a car (air conditioning, opening driver’s window and positioning the cigarette at that opening when not puffing) still left the levels of secondhand smoke at hazardous and unhealthy levels.

2.1 This and other similar studies have led eight of the ten provinces in Canada and one of the three territories to pass laws banning smoking in cars with children. The Canadian experience with such laws has been extremely positive: results from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Survey in Canada has shown that over 80% of adult smokers support banning smoking in cars with children and similar levels of support have been found in the UK.

2.2 The conclusions are that:

- it is established that SHS is dangerous to humans, particularly to children;

- there are very high levels of SHS in cars, even when the typical strategies to reduce smoke are employed;

- most Canadian provinces have passed a ban on smoking in cars containing children, and Canadian smokers have been very supportive, with support continuing to increase;

- support among adult smokers in the UK is continuing to climb; it is now over 80%.

5.3 Private member’s Bill

Activity 4 demonstrated the use of a pressure group and how they can influence the introduction of a private member’s Bill. There are a number of ways in which a private member’s Bill may be proposed and introduced to the House of Commons:

- A ballot procedure allows a maximum of 20 back-benchers. A back-bencher is a member of parliament who is currently not a member of the Cabinet and does not hold a ministerial post but may propose new legislation. However, the timeframe for Parliament to process new legislation means that there is only a small quota of legislation allowed to be introduced by back-benchers. At the beginning of each parliamentary session the 20 members who were successful in the ballot are allowed to present their proposed legislation. Each of the private members’ Bills are usually discussed on a Friday and given a provisional date for a second reading or any further stages to be undertaken. These Bills may be of a controversial nature and they tend to relate to a member or a group of members who have a connection with the subject matter. The majority of private members’ Bills are usually done through the ballot procedure.

- Ten minute rule Bills are allowed under Standing Order No. 23. This order allows members to gain permission to introduce a Bill. The ten minute rule allows members to introduce a subject matter and a proposed change in the law. This process is usually taken up just after question time on a Tuesday. The ten minute rule was used by the MP Alex Cunningham to introduce a Bill which proposed a ban on smoking in private vehicles where there are children under the age of 18 years old present. Pressure groups such as the British Lung Foundation (BLF) have supported this proposal through their campaign against smoking in cars where children are present.

- An MP is permitted to introduce a Bill after giving notice under what is known as Standing Order No. 57. This type of Bill cannot be presented until after all the ballot bills have been presented and they have reached the second reading stage.

An example of a private member’s Bill becoming law is the Abortion Act 1967 (as amended by later legislation), which was introduced as a private member’s Bill by the then Liberal MP David Steel: this is still the law governing abortion in England, Scotland and Wales today, though it has been amended on several occasions.

5.4 Agencies of reform

There are various agencies of reform, such as the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC), which monitor and evaluate current legislation. This independent body was created by the Criminal Appeal Act 1995. The CCRC monitors and reviews any possible miscarriages of justice and reviews the legal rules and process dealing with criminal cases. The Law Commission is another independent agency of reform which was created through a piece of legislation, the Law Commission Act 1965: the Law Commission monitors and reviews the law. It puts forward proposals to reform the law where there is a current problem with legislation or a need to introduce new legislation. The Law Commission tries to ensure that the law is fair, cost-effective and up-to-date with current practice. The Law Commission produces a number of papers which are referred to as Command Papers. These papers outline the current law (legislation), any perceived problems, recommendations and draft legislation for any changes to be implemented.

Activity 5 Evaluating and monitoring the law

Look at the ‘Forfeiture Rule and the Law of Succession’ consultation on the Law Commission website. To access this once you are on the website, click on the ‘Consultations’ tab and then on ‘A–Z of consultations’. This will provide you with a number of topics which have been reviewed or are under current review. Click ‘F’ and then click ‘Forfeiture Rule and the Law of Succession’. You only need to read the first page of this project, which will provide you with some information about the report and what might be considered to be wrong with the law.

In no more than 200 words, explain the role of the Law Commission and provide some information about the Forfeiture (Succession) Report.

Comment

The role of the Law Commission is to monitor and review the law. It undertakes a review of a specific subject area and through a consultation paper consults with the public and professional bodies by seeking views and advice. The Law Commission produce a report, referred to as a command paper, which outlines the current legal rules and identifies any potential problems. They then put forward a number of recommendations and include a draft piece of legislation for the government to consider. The government then arranges for this draft legislation to be introduced into Parliament for debate by both Houses.

The Forfeiture Rule and the Law of Succession Report would have informed you that:

There is a rule of law, known as the forfeiture rule, which states that a person may not inherit from someone whom he or she has unlawfully killed. In 2000 the Court of Appeal decided that the forfeiture rule, when applied alongside the rules on intestate succession, disinherits not only the killer, but also the killer’s descendants.

You are informed at the beginning of the report that the recommendations of the Law Commission have been accepted by Parliament and have now been implemented through new legislation: the Estate of Deceased Persons (Forfeiture Rule and Law of Succession) Act 2011.

5.5 White and Green Papers

You may come across the terms ‘White Papers’ and ‘Green Papers’ when dealing with proposed legislation. These Papers are consultation papers produced by the government, which outline changes to existing legislation or government proposals that are still taking shape and are seeking comments from the public. A Green Paper refers to suggested reforms in the law and a White Paper outlines the proposals that are going forward and will appear in draft legislation, known as a Bill. There is no requirement for White or Green Papers to be produced before a Bill is introduced into Parliament but they are common when it comes to implementing government policy.

Activity 6 Democracy revisited

Watch this short film which highlights some of the points identified in the previous sections of this course. Make some personal notes for yourself and try to identify the reasons why we have a democracy, how a democracy is achieved in the UK and why we have legal rules.

Transcript: Activity 6 Democracy revisited

[EXHALING]

[JEERING]

[BOUNCE]

[GLASS BREAKING]

[SLAM]

[SQUIRT]

Comment

Democracy, in theory, ensures everyone is treated fairly in the sense that power is not in the hands of one person or government body. The distribution of power in the UK is through a general election which allows citizens in the UK to vote for their chosen parliamentary candidate. This system enables the political party with the most votes to acquire the most seats (MPs) in the Westminster Parliament. It is MPs who represent the UK citizens in Parliament and in this way there is a process that is designed to reflect the views of society when considering, discussing and passing new legislation.

6 Draft Bills and pre-legislative scrutiny

A Draft Bill is a Bill that is published to enable consultation and pre-legislative scrutiny before a Bill is formally introduced into either the House of Commons or the House of Lords. The short film below outlines how voting takes place when dealing with a Bill and some of the parliamentary procedures that take place, such as calling MPs and Lords to vote by sounding the division bell.

Transcript: Draft Bills and pre-legislative scrutiny

6.1 How statute law is made

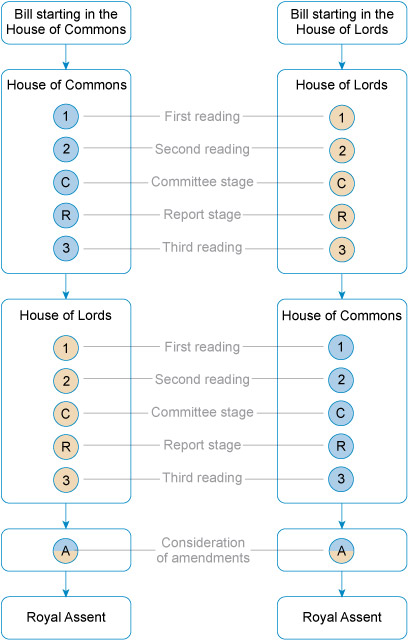

Legislation is proposed, presented and made in the Westminster Parliament. As outlined earlier, the Westminster Parliament is made up of two chambers (Houses) and the monarch. Proposed legislation is known as a Bill, which is also referred to as draft legislation and must be debated by both Houses through a set of stages that are referred to as:

- First reading

- Second reading

- Committee stage

- Report stage

- Third reading

- Royal Assent.

This process takes places in both Houses and if the Bill starts in the House of Commons it passes to the House of Lords once it has completed all its stages. In the House of Lords it then goes through the same stages from first to third reading. It is then passed back to the House of Commons with any comments or suggested amendments. This latter stage is known by the term ‘ping pong’ as the Bill goes back and forth between the two Houses.

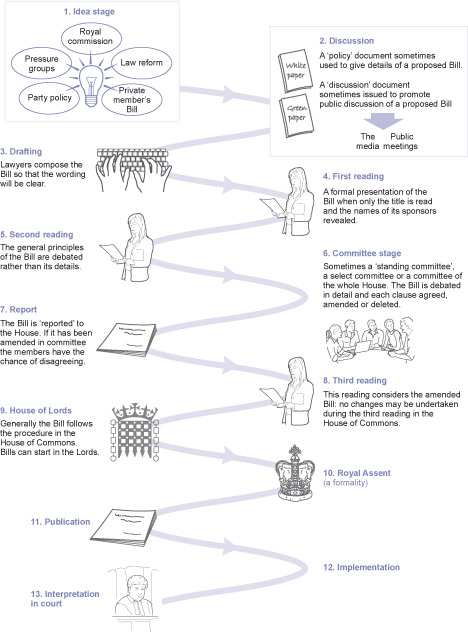

Before considering each of these stages, take a look at the following diagram, which tries to capture all the possible stages that take place before a proposed piece of legislation becomes a Bill and eventually an Act of Parliament. Consulting the diagram will help you to visualise the process when you read the next section of this course.

This is a picture which illustrates how law is made from inception through to becoming law. There are a number of stages which are numbered from 1 to 13. Stage 1 starts at the top and Stage 13 is at the bottom. Each numbered stage compartmentalizes each part of the process by using a picture which captures each stage of the law-making process and accompanying text.

Picture 1 is of a light bulb, which symbolizes an idea that has been generated by a number of individuals or government bodies, such as the Royal Commission (an agency of law reform), a pressure group, a party policy that has been put forward as new legislation, a private member’s Bill or an alternative law reform body such as the Law Commission.

Picture 2 is of a White Paper and a Green Paper. These are discussion documents that are used to give details of proposed legislation.

Picture 3 is of a keyboard and a pair of hands typing the draft of a new piece of legislation. This is the drafting of the Bill to make sure that the wording of the proposed legislation is clear.

Picture 4 is of a woman reading out the Bill at the first reading process, which is the introduction of the proposed legislation.

Picture 5 is of a woman reading out the Bill for the second time. At this stage the Bill is outlined.

Picture 6 is of a number of individuals sitting around a table. This represents the committee stage. This is where the Bill is debated by a committee and any agreed amendments are made.

Picture 7 is of a report. This represents the report stage, which informs either the House of Lords or House of Commons of any amendments.

Picture 8 is of a woman reading out the Bill for the third time.

Picture 9 is of a portcullis with a crown above it. At this stage the Bill passes to the next House. If the Bill started in the House of Commons, the next House would be the House of Lords.

Picture 10 is a picture of a crown which is symbolic of the Royal Assent.

Picture 11 is a picture of the published legislation.

Picture 12 simply states that the legislation is being implemented.

Picture 13 is a picture of a judge in a court who is reading the legislation, interpreting the rules and applying them.

6.1.1 First reading

The first reading is the reading out of the title and identifying the date for the second reading. The Bill is then published and made available for members of the House who will have an opportunity to debate the Bill at the second reading.

6.1.2 Second reading

A spokesperson or government minister will be made responsible for the Bill and will introduce the Bill at the second reading. Once the minister has outlined the Bill and made any specific points there will be an opportunity for the opposition parties to give their opinions on the Bill. There may be support and opposition to the Bill and this depends on the nature and purpose of the Bill. At the end of the second reading the House votes on whether to support the Bill or oppose it. If the majority of MPs support the Bill it will then proceed to the next stage, which is the committee stage.

6.1.3 Committee stage

The committee stage is where the Bill is scrutinised and also where any amendments usually take place. The committee’s role is to examine each clause (paragraph) of the Bill, and if the Bill was first presented to the House of Commons, at this committee stage evidence may be provided by experts or any external pressure groups. There will be an appointed chairperson of the committee and a designated number of members of the committee who will be responsible for the examination of the clauses. The chairperson may select and put forward an amendment at this stage, which must be passed by a majority vote taking place among the members of the committee. Once all the amendments have been undertaken the Bill is re-drafted and printed. It is then returned to the House for the report stage.

6.1.4 Report stage

The report stage provides MPs with an opportunity to consider the changes that have been undertaken at the committee stage. It also allows them to put forward any further amendments. The third reading usually takes place straight after the report stage.

6.1.5 Third reading

This reading considers the amended Bill: no changes may be undertaken during the third reading in the House of Commons. There is then a vote and if the majority of MPs vote in favour of the Bill it is passed to the House of Lords for its first reading: it then follows a similar process as outlined above.

Once there is mutual agreement by both Houses the final version of the Bill can receive Royal Assent. It is only upon receiving Royal Assent that the Bill will become an Act of the Westminster Parliament. The Act (statute) will either become law immediately or a date will be set for when the Act will come into force. Occasionally, the House of Lords will not agree the final amendments, and the Bill falls. However, the Parliament Acts may be utilised and this will allow the House of Commons to pass the Bill without needing the House of Lords’ consent.

6.1.6 A Bill

Figure 6 outlines the passage (stages) a Bill must go through before it becomes law. The Bill may start off in the House of Commons or House of Lords, but it must go through both Houses before it becomes law.

This figure illustrates the passage of a Bill through the House of Lords and House of Commons. It outlines the procedure from first reading, second reading, committee stage, report stage to third reading. Once this process has been followed it is then passed to the next chamber. If the Bill starts in the House of Commons, it is passed to the House of Lords chamber: this is illustrated by showing that the same process takes place as in the House of Commons. The figure demonstrates that once the Bill has passed through all of these stages in both the House of Lords and House of Commons, it then receives Royal Assent.

To see short explanations of each stage, consult the UK Parliament website.

6.2 An Act of Parliament

Having considered the various stages a Bill must go through before it becomes law, in the next activity it is time to have a look at a piece of legislation.

Activity 7 Concentrate on contracts

Read the first page of the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977:

The text on the first page of the Unfair Contract Terms Act 1977 reads:

An Act to impose further limits on the extent to which under the law of England and Wales and Northern Ireland civil liability for breach of contract, or for negligence or other breach of duty, can be avoided by means of contract terms and otherwise, and under the law of Scotland civil liability can be avoided by means of contract terms.

Be IT ENACTED by the Queen’s most Excellent Majesty, by and with the advice and consent of the Lords Spiritual and Temporal, and Commons, in this present Parliament assembled, and by the authority of the same, as follows:—

Part I

Amendment of law for England and Wales and Northern Ireland

Introductory

1.— Scope of Part I

- For the purposes of this Part of this Act, ‘negligence’ means the breach—

- a.of any obligation, arising from the express or implied terms of a contract, to take reasonable care or exercise reasonable skill in the performance of the contract;

- b.of any common law duty to take reasonable care or exercise reasonable skill (but not any stricter duty);

- c.of the common duty of care imposed by the Occupiers’ Liability Act 1957 or the Occupiers’ Liability Act (Northern Ireland) 1957.

- This Part of this Act is subject to Part III; and in relation to contracts, the operation of sections 2 to 4 and 7 is subject to exceptions made by Schedule 1.

- In the case of both contract and tort, sections 2 to 7 apply (except where the contrary is stated in section 6(4)) only to business liability, that is liability for breach of obligations or duties arising—

Now write out in your own words what you think the Act is trying to achieve.

Comment

Its purpose is to control the use of the exclusion or limitation clauses that have been incorporated into a contract.

6.3 Reading a statute

The layout and structure of a statute follows a specific order. As part of this course you need to be able to refer to the areas within a piece of legislation. Below you are provided with an outline of the structure of a statute.

- Title

- Citation – chapter number

- Long title

- Date of Royal Assent

- Sections.

7 Enabling legislation

Earlier, you were introduced to the stages a draft piece of legislation goes through in order to become an Act of Parliament. Enabling legislation (primary legislation) follows the same process but the content of the legislation has not been fully outlined in the Bill. Rather, it outlines the nature of the legislation and explains what it wants to achieve. It is referred to as a parent Act or enabling Act as it confers powers to a government minister or ministerial body to develop the details of the legislation at a later date. This form of legislation is known as delegated or secondary legislation as it delegates the task of putting the flesh on the framework to a government minister or ministerial body. An example of delegated legislation is referred to as a statutory instrument (SI). An SI allows a government minister, such as the health minister or social security minister, to develop the legislative rules while implementing government policy. The minister is given the power to do this under the enabling Act and this is lawful as long as the minister operates within the powers (intra vires) of the enabling Act. Occasionally, a minister may be accused of abusing this power by acting outside the powers (ultra vires) of the enabling Act. The process for such an investigation is referred to as a judicial review. If this allegation is proven then the rules, codes or statutory instruments would not be lawful.

7.1 So, why do we have delegated legislation?

Delegated legislation enables a government to change the rules (law) by using the powers provided by the primary legislation (enabling Act), such as statutory instruments which are drafted (written) by government departments. Much of the delegated legislation created in England and Wales is created in the form of statutory instruments.

Activity 8 Legislating for legislation

Read the following article (Pywell, 2013). While reading this article try to identify the different types of delegated legislation and in your own words explain the differences between these various types of delegated legislation.

Comment

The details in this article explain the different types of delegated legislation, such as statutory instruments, bye-laws and orders in council. You will have noted the author’s criticisms about the way delegated legislation has been labelled and how this can be misleading. The table provided in the article summarises the different types of delegated legislation and explains where they originated from.

8 Devolution – transfer of powers

This is a map of the United Kingdom. It shows Scotland, Northern Ireland, England and Wales and their capital cities.

Figure 8 is a map of the United Kingdom, which identifies the four different countries that constitute it. In this part of the course you will explore the concept of devolved power from the Westminster Parliament to the recognised bodies of the Welsh Assembly, Scottish Parliament and Northern Ireland Assembly.

Devolution is the transference of power from central government to local government. Since 1999 the decentralisation of power from the Westminster government has taken place. Certain matters that were once dealt with in London are now distributed to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Since devolution has taken place we now have the Welsh Assembly in Cardiff, the Northern Ireland Assembly in Belfast and the Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh.

Watch this short film, which provides some additional information on devolution and outlines some of the powers that have been transferred to different parts of the UK.

Transcript: Devolution – transfer of powers

As this course is discussing the law that governs England and Wales, the focus will be on devolution in Wales.

8.1 Devolution in Wales

The political roots for devolution in Wales originated in 1886 when a body known as Cymru Fydd (Young Wales) was created by the Liberal political party, which was asking for home rule in Wales. The transfer of power from Westminster to Wales has been a slow process and it was not until 1964, after a general election, that the role of the Secretary of State for Wales was created and the Welsh Office was established in Cardiff. Yet, all law-making processes took place in the Westminster Parliament. It was not until May 1997, when the Labour party won the general election, that a referendum was arranged. The referendum asked the people of Wales whether they wanted their own assembly. The result of the referendum in July 1997 was 50.3% in favour of a Welsh Assembly and 49.7% against it. The result triggered a White Paper, which was called ‘A Voice for Wales’: it was published on 18 September 1997 and outlined the need for a Welsh Assembly and its law-making powers. This was debated in the House of Commons by the then Secretary of State for Wales, Ron Davies. The extract below has been taken directly from Hansard, which is the official transcript of the proceedings. It is easy to see why the Secretary of State was in favour of a Welsh Assembly.

Box 2 The road to devolution

22 Jul 1997 : Column 757

Welsh Assembly

3.30 pm

The Secretary of State for Wales (Mr Ron Davies): With permission, Madam Speaker, I should like to make a statement about the Government’s proposals for creating an Assembly for Wales. The Government believe that, in the United Kingdom, too much power is centralised in the hands of too few people. We believe that there is too little freedom for people in each part of the United Kingdom to decide their own priorities. Our manifesto made clear our intention to give Britain a modern constitution fitting a modern and progressive country. We believe that it is right to bring decisions closer to people, to open up government, to reform Parliament and to increase individual rights.

The White Paper [‘A Voice for Wales’] that I am publishing today marks a major step forward in the achievement of our proposals for Wales. We propose to create a democratically elected Assembly that will give the people of Wales a real say in the way public services in Wales are run.

Since the Welsh Office was set up more than 30 years ago, there has been a progressive devolution of administration to Wales. As Secretary of State for Wales, I am responsible for taking decisions about health, education, economic development, roads, planning and many other public services that matter to people’s everyday lives. I am accountable to the House, but our procedures here are too often seen as remote from the day-to-day realities of devolved administration.

This was the road to devolution, which was slowly being carved out for Wales. In the next sections you will see how the limited law-making powers within Wales have now been transformed to full law-making powers.

8.2 The call for a Welsh Assembly

The call for a Welsh Assembly was stronger than ever and the referendum in Wales had confirmed the need for a separate law-making body in Wales. However, it would seem that the law-making powers for the Assembly in Wales were being curtailed. Take a look at the following quote, which has been taken directly from the Constitution Unit, School of Public Policy, which produced a paper commenting on the White Paper ‘A Voice for Wales’:

The Welsh Assembly will have no law-making power, but will take over the executive responsibilities currently exercised by the Secretary of State for Wales (health, education, local government, transport, agriculture, industry and training etc.). In these policy areas the Assembly will operate within a legislative framework set by Westminster. Within this framework it will have power to make rules and regulations by secondary legislation.

This statement summed up the position of the Welsh Assembly as a law-making body. It was clear that the Welsh Assembly had a voice but the script was still being written by the Westminster Parliament: all legislation was still being created by the Westminster Parliament and then discussed by the Assembly Members in the Senedd (Senate).

8.3 The creation of the Welsh Assembly

In 1998 the Government of Wales Act created the National Assembly for Wales as a single corporate body. This in effect provided the Assembly with the right to create secondary legislation and have 60 Assembly Members (AMs). However, in 2006 the Government of Wales Act (GOWA) was passed in the Westminster Parliament and transferred power to the Welsh Assembly to make its own law (primary legislation) within a number of specific areas, such as education and health. This means that the laws passed in the Westminster Parliament still apply to Wales but certain subject areas are now transferred to the Welsh government that resides in the Welsh Assembly in Cardiff.

This figure is a picture of the Welsh Assembly (Senedd), which is located in Cardiff. It shows the front of the building and entrance to the Assembly.

The Welsh Assembly, which includes the 60 AMs, is the legislature for Wales, alongside the Welsh Government, which includes the First Minister, Deputy Ministers, Ministers (in the Cabinet), and the Counsel General. It is important to note that the legislature is separate from the Welsh Government, which is known as the executive. This recognises the separation of powers between the legislatures, which includes all AMs from different political parties. Just like the UK government, the political party that holds the majority of seats in the Welsh Assembly forms the government. The function of the Welsh Government is to consider and implement policy decisions through the legislative process, whereas the Welsh Assembly legislature (all the AMs) scrutinise proposed legislation being put forward by the Welsh government: this reflects the same process that takes place in the Westminster Parliament when new legislation is being debated.

Activity 9 Constitutional considerations

Below is an extract from a journal article by Peter Leyland (2011), ‘The multifaceted constitutional dynamics of UK devolution’. Read this extract and make some notes.

The most limited form of devolution was devised for Wales.1 Although Wales retained its distinctive language and culture when originally brought into the U.K., from the standpoint of law and administration it lacked Scotland’s distinctive legal and education system and Wales was more integrated with England. Moreover, it was clear when devolution was introduced that there was much less popular support for this change in Wales.2 However, the limitations of the Government of Wales Act 1998 were such that the devolved institutions in Wales have already been granted additional powers following the passage of the Government of Wales Act 2006. The major original difference was that the Welsh Assembly, unlike the Scottish Parliament and Northern Ireland Assembly, was not granted the power to pass legislation in its own right. The fact that Welsh Bills had to take their place in the queue before being shepherded through the Westminster Parliament by the Welsh secretary was regarded as a serious drawback.3 Otherwise the Welsh Assembly only had the power to pass secondary legislation.4 In consequence, there were almost immediate calls after devolution to give the Welsh Assembly the power to pass laws.5 The Westminster government responded by granting the Assembly powers to propose a form of law known as a ‘Measure of the National Assembly of Wales.’6 These measures are enacted by first receiving scrutiny and approval by the Assembly and, then, the measure is referred to the Westminster Parliament for approval by resolution of each house before being recommended as a new form of Order in Council.7 This procedure created a special form of delegated legislation which potentially could be vetoed at Westminster. However, in practice, the new procedure overcame the problem of securing the passage of legislation required for Wales through the Westminster Parliament. The revised arrangements for Welsh legislation might have proved problematic if there was a strong conflict of wills between the Welsh Assembly and the government in power at Westminster—for example, if different political parties had a majority in the Assembly and at Westminster. In another sense, these measures to enhance the lawmaking capacity of the Welsh Assembly8 have a wider, incidental impact, as there is now distinctively ‘English’ legislation introduced before the Westminster Parliament.9 A referendum in accordance with the provisions of the Government of Wales Act 2006 was held in March 2011 which approved by a large majority (63.5 per cent for with 36.5 per cent against) the conferral of full legislative powers upon the Welsh Assembly.10 In consequence, the Welsh Assembly in common with the Scottish Parliament and Northern Ireland Assembly will soon have powers to pass legislation concerning the policy areas which fall under its competence.

There are some obvious parallels between Scotland and Wales with respect to the electoral system and the organization of the legislative and executive bodies.11 The Government of Wales Act 1998 set up a single chamber Assembly for Wales, consisting of sixty members12 who must be elected every four years by an additional member system. Each elector is given two votes. Assembly members for each constituency are returned by simple majority, while the four Assembly members for each region are returned by a system of proportional representation based on party lists.

In common with Scotland, the Welsh Assembly is required to form policy and take decisions in its particular areas of responsibility. Also, as in Scotland, the cabinet style of government is formed following an election. The newly elected members of the Welsh Assembly vote for a first minister. Once elected, the first minister has the power to appoint an Executive Committee of Assembly Secretaries, which forms the equivalent of a cabinet. The ministerial portfolios of this executive committee (the combinations of policy areas allocated to the individual assembly secretaries) determine the areas of competence of the scrutiny committees (or subject committees) that are subsequently formed to provide executive oversight. The appointments to the executive committee can be from a single party or a combination of parties.

As with Scotland, the Welsh executive took over, by means of transfer orders, most of the administrative functions of the secretary of state for Wales under the Government of Wales Act 1998.13 Cabinet members have the equivalent of departmental responsibility for their given policy areas. Although the National Assembly of Wales was formed as a single corporate body, a de facto division emerged postdevolution between the Welsh Assembly government and the Welsh Assembly as a representative body. The Welsh Assembly government has been recognized under the Government of Wales Act 2006 as an entity separate from, but accountable to, the National Assembly. One significant difference between the approach to devolution in Scotland and Wales is that while the Scottish Parliament was granted general competence, subject to the reserved matters under the Scotland Act, in the case of Wales powers were conferred according to particular areas of policy.14 The Assembly and executive are also responsible for many Welsh nondepartmental governmental organizations, funded and appointed by government. 15

From this brief discussion, it will be apparent that there are clear parallels between the general frameworks of Scottish and Welsh devolution, including, for example, the method of election and the way a devolved executive is formed. This resemblance will grow a great deal closer should the proposal to give the Welsh Assembly full lawmaking powers gain the approval from the Welsh electorate in 2011. However, the Welsh Assembly has no devolved tax-raising powers (unlike the proposals for Scotland), and no such powers are in immediate prospect.

Notes

1 For a compelling study of the parameters of Welsh devolution, see Richard Rawlings, Delineating Wales: Constitutional, Legal and Administrative Aspects of National Devolution (2003).

2 The margin in favor of Welsh devolution in the referendum was less than 0.2 percent.

3 Richard Rawlings, Law Making in a Virtual Parliament: the Welsh Experience, in Devolution, Law Making and the Constitution (Robert Hazell & Richard Rawlings, eds., 2005).

4 Otherwise the Welsh Assembly only had the power to pass secondary legislation.

5 See the Richards Commission.

6 Government of Wales Act 2006, s. 93.

7 GWA 2006 s. 94. Orders in Council are usually secondary legislation issued under powers in a parent act, and they are often used for transferring powers and responsibilities.

8 See Better Governance for Wales, Cm. 6582, 2005.

9 Whereas English and Welsh legislation were often combined the introduction of Assembly Measures with a different procedure means that the Westminster Parliament now passes legislation which only applies to England. This trend will be accentuated as the Welsh Assembly acquires its own law-making powers. See Richard Rawlings, Hastening Slowly: The Next Phase of Welsh Devolution, Pub. L. 824–852, 841 (2005).

10 GWA 2006 s. 104 and s. 105. See http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-politics-12648649.

11 GWA 1998, ss. 3–7.

12 An obvious reason why the Welsh Assembly has fewer members than the Scottish Parliament is because Wales has a smaller population.

13 GWA s. 22(2) and schedule 2.

14 The principal matters devolved are: agriculture, forestry, fisheries and food, environmental and cultural matters, economic and industrial development, education and training, health, housing, local government, social services, sport and tourism, town and country planning, transport, water and flood defenses, and the Welsh language.

15 For example, the Welsh Health authorities and the Welsh Tourist Board.

Could the Welsh Assembly make its own legislation?

Comment

The Government of Wales Act (GOWA) 1998 only allowed the Welsh Assembly to create and implement legislation after it had first obtained permission from the Westminster Parliament. The system operated through what was known as obtaining ‘legislative competence’, which meant that for the Welsh Assembly to be able to make legislation on a specific area this must first be approved either in a Westminster Bill (later a statute) or through an Order in Council process which is sanctioned by the GOWA. Once the legislative competence had been given to the Welsh Assembly this right became a continuing one and there is no need to seek future permission to legislate on this area again. This meant that the Welsh Assembly only had the right to go ahead and formulate new legislation if it had first been approved by the Westminster Parliament. An example is the Welsh Assembly’s right to create its own legislation dealing with special educational needs in Wales. In effect the Welsh Assembly was building up a large selection of areas which had been devolved to them and this enabled them to create new legislation as and when it is necessary without the need to seek further permission.

The laws that were previously passed by the Welsh Assembly were referred to as measures and not statutes. Measures are primary legislation but still need to be approved by the monarch, just as a statute receives Royal Assent. The introduction of an Assembly Measure had the same effect as a statute passed by the Westminster Parliament. There are some restrictions which are outlined in Part 3 of the GOWA but otherwise the Welsh Assembly has devolved powers to make its own legislation in certain areas. However, in 2006 the Government of Wales Act (GOWA) was passed in the Westminster Parliament and transferred power to the Welsh Assembly to make its own law (primary legislation) within a number of specific areas, such as education and health. This means that the laws passed in the Westminster Parliament still apply to Wales but certain areas are now transferred to the Welsh government that resides in the Welsh Assembly in Cardiff.

8.4 Stages of a proposed piece of legislation in the Welsh Assembly

A Welsh Assembly Measure goes through a similar process as a Bill goes through in the Westminster Parliament but the terminology is different. Before a proposal becomes law it must go through five stages:

- Members of the Welsh Assembly (referred to as AMs – Assembly Members) consider and agree in principle on the Measure.

- A detailed consideration of the Measure. This involves a selected committee of AMs amending the Measure.

- A debate which takes place in the chamber of the Assembly. This provides an opportunity for AMs to debate the proposed legislation and involves all AMs from different political parties.

- Passing the final draft of the Measure to the National Assembly for consideration. The final draft of the Measure is also passed to the monarch at the Privy Council. The Privy Council is a legislative assembly which has executive responsibilities. It originated during the reign of the Norman Kings and meetings were then held in private, hence the name ‘privy’.

- The announcement when the Measure will come into force.

8.5 The referendum in Wales – to make its own laws

On 3 March 2011 a referendum took place in Wales. The people of Wales were asked if the Welsh Assembly should be allowed to pass its own legislation. The outcome of the referendum was positive: this means that the 20 devolved fields, which deal with specific areas such as health and education, no longer need further approval from the Westminster Parliament in order to create new laws. It also means that the terminology has changed. Instead of using the phrase ‘measures’, the Welsh Assembly considers new legislation in the form of a Bill, which if passed will become a statute. This means that the Welsh Assembly has gained additional powers and reflects the same law-making process as that carried out in the Westminster Parliament.

Activity 10 Referendum: key questions

This activity will reinforce the points made above and allow you to consider the changes that have taken place.

Watch the following two films, which provide a short overview of the referendum in Wales. These films outline the changes that have taken place since March 2011. The Welsh Assembly is now allowed to make its own legislation in any of the 20 devolved fields.

Transcript: Activity 10 Referendum: key questions (video 1)

Transcript: Activity 10 Referendum: key questions (video 2)

[MUSIC PLAYING]

Conclusion

This course has considered the notion of democracy and how the laws passed in Parliament should reflect the will of the people. However, as you will have gathered, the democratic process does not always reflect everyone who casts their vote during a general election. If the UK were to adopt a different election system such as proportional representation (PR), this would go some way to ensuring that everyone’s vote counts. However, this system can potentially cause problems, such as a hung parliament, which means there is no majority party and that it would be difficult to pass any new legislation.

You are now familiar with the stages a Bill goes through and how it becomes an Act of Parliament. This is a lengthy process and the type of legislation that is usually introduced is a public Bill that reflects the majority party’s manifesto and political persuasion. This in itself can cause some contention within society as people in the nation will have different political persuasions and not always feel as if they are being represented through a democratic process – that is, that democracy is a mere notion.